Is it peace (Ma nabad baa)? Not really. Despite progress over the past few decades, Somalia continues to grapple with terrorism, humanitarian crises and domestic struggles over federalism and security governance. Peace also remains elusive among Somalia’s international partners, as agreement on financing for the newly established African Union Support and Stabilisation Mission in Somalia (AUSSOM) is yet to materialise.

Authorised by the UN Security Council (UNSC), AUSSOM officially began operations in January 2025 . Hailed as a test case for AU-led peace support operations with UN financing, it is already hamstrung by funding woes. Disputes over the implementation of UNSC Resolution 2719, allowing for up to 75% UN financing, persist. With US opposition hardening under the new administration, the model for AU-led peace operations faces the risk of prolonged stagnation. Donor fatigue looms large, with the European Union – historically the AU’s chief backer in Somalia – showing signs of weariness. The lure of bilateralism and mounting AU frustration over a decade of stalled funding discussions add to the uncertainty. With a decision due by May 2025, Somalia and its partners must focus on the essential task at hand: averting a security vacuum.

New mission, old hurdles?

Since 2007, the AU has deployed three missions to Somalia. After the civil war, failed UN and US interventions in the 1990s, and the brief rule of the Union of Islamic Courts, Somalia reemerged in global discussions. The African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM), initially conceived as a peacekeeping mission with little peace to keep, quickly evolved to include counterinsurgency tasks against al-Shabaab, an al-Qaeda affiliate since 2012. In 2022, AMISOM was rebranded as the African Union Transition Mission in Somalia (ATMIS), which focused on maintaining security gains and gradually handing over control to Somali forces.

And finally came AUSSOM. Its mission is to support the Somali Federal Government in preserving security gains and strengthening its security forces. But it seems to have inherited ATMIS’s financial woes, as the latter concluded its operations with a funding shortfall of about €96 million.

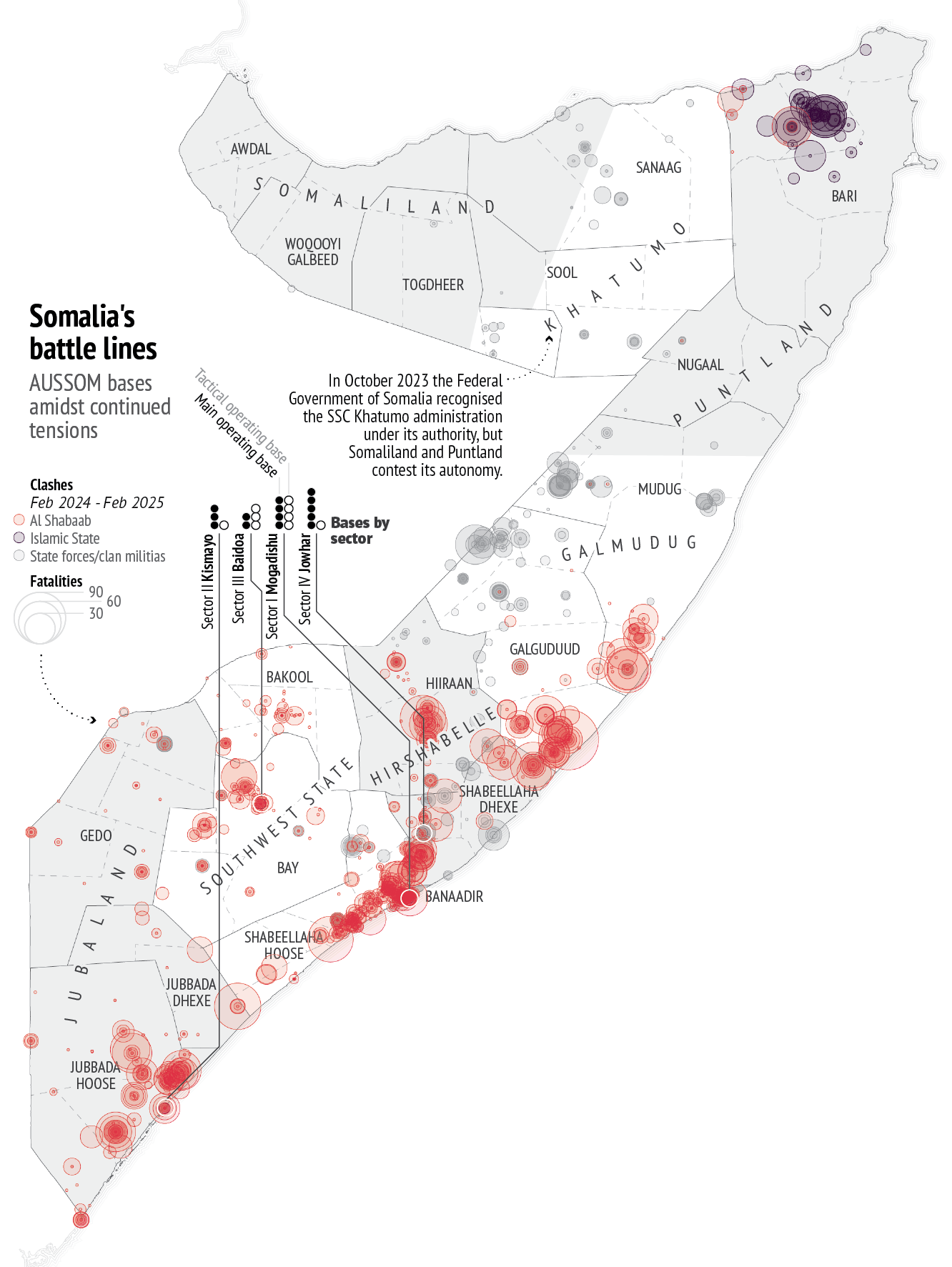

As discussions at the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) stall, largely due to US concerns over using UN-assessed contributions, AUSSOM faces a difficult start. The Biden administration supported a transitional funding mechanism instead of fully implementing UNSC Resolution 2719 and urged continued EU financial backing for the AU mission. The Trump administration will probably take a different approach, steering further away from multilateralism. However, US interests in Somalia’s stability and counterterrorism remain clear. In 2025 US Africa Command continued airstrikes against the Islamic State and al-Shabaab as a core part of its mission.

Financing is not the only challenge that AUSSOM has faced. Disagreements among troop-contributing countries delayed force generation until February 2025. Initially Somalia rejected Etiopian troops following the Ethiopia-Somaliland memorandum of understanding of January 2024, while Egypt pledged its forces to the mission. However, a Türkiye-brokered agreement in December 2024 eased tensions between Ethiopia and Somalia, facilitating Ethiopia’s contribution to AUSSOM. Burundi, a long-standing contributor to AU missions in Somalia, diverged with the Somali government over troop numbers and withdrew its pledge at the end of 2024.

As of February 2025, Djibouti, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda are expected to deploy troops to AUSSOM, together with police personnel from Egypt, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone. On 30 June, AUSSOM should conclude troop realignment from ATMIS. Its success will largely depend on securing adequate financing.

The risk of bilateralism

International donors have engaged with Somalia at various stages. Since 2007, the EU has invested about €4.3 billion in Somalia’s security, including personnel costs for AMISOM and ATMIS. It also contributes through three CSDP missions and operations, combining more traditional military engagements (EUTM Somalia) with efforts to combat piracy (EUNAVFOR Atalanta) and strengthen the rule of law. Additionally, it has focused on civilian capacity building for security forces, which are crucial for stabilisation efforts, especially in areas reclaimed from al-Shabaab, and for the transition towards establishing state services to the population. For instance, EUCAP Somalia is training the Darwish, a gendarmerie force that can consolidate security gains in reclaimed areas and help establish state services and authority.

The UN has played a key role through the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM), which provided policy advice on peacebuilding and state building. However, at Somalia’s request, UNSOM’s mandate ended on 31 October 2024, with its responsibilities transferred to the United Nations Transitional Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNTMIS), set to conclude by October 2026 and transfer all functions to the UN Country Team. In contrast, the United Nations Support Office in Somalia (UNSOS) remains crucial for logistical support to AU peace support operations. In fact, a key issue in the UNSC discussion on UN-assessed contributions is whether UNSOS funding falls within the 75% cap on such contributions. The US spent about €2 billion in funding for AMISOM and Somali security forces between 2007 and 2020.

Other partners like the Gulf countries and Türkiye have progressively deepened their engagement in Somalia and in the Horn of Africa. Beyond military bases, commercial ports and defence agreements, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Türkiye have regularly trained and funded Somali security forces. Since 2010, the UAE has supported the Puntland Maritime Police Force (PMPF), a new federal military police unit, several army brigades, and deployed trainers to Somalia. In addition, it has financed associated costs for the PMPF, estimated at about €48 million per year, and personnel costs for the new brigades, estimated at approximately €8.6 million per month. Since 2011, Türkiye has also increasingly looked at Somalia as a gateway to Africa, expanding its foreign policy influence through significant investments in economic, humanitarian, development, mediation and security initiatives, including the training of 6 000 Somali soldiers at Camp Turksom in Mogadishu as of 2024.

As UNSC negotiations on implementing UNSCR 2719 face challenges, countries such as Türkiye, the UAE, the US and Ethiopia are increasingly turning to bilateral agreements to broaden their influence, support the Somali government, and advance their own economic and security interests. However, while bilateral agreements can provide complementary support, they cannot replace an overarching multilateral framework that could ensure interoperability of forces, and avoid duplication or even competition. In addition, relying on multiple bilateral partnerships forces the state to engage with numerous external actors, diverting attention from crucial domestic reforms, including constitutional revision, the national census, and integration of different forces into the national security architecture.

While bilateral support can aid the transition between AU missions, it must not come at the expense of Somali governance. If left unchecked, fragmented donor engagement could undermine past progress, deepen internal divisions, and lead to destabilising consequences.

The Somali challenge

Over the past 20 years, Somalia has made significant progress. The 2012 provisional constitution launched federalism and allowed for the gradual establishment of regional states. It also introduced security sector reforms, expanded Somali security forces, and created a security architecture. Despite relying on an indirect clan-based system, Somalia’s elections have enabled periodic changes in leadership. Additionally, in 2023 the country announced its first population census since 1986, a crucial step towards future direct elections.

However, disputes between the Somali federal government and member states over power-sharing, authority and resource distribution persist. These tensions have lately been further compounded by disagreements over the feasibility of a ‘one-person-one vote’ election for 2026. The federal government faces ongoing challenges, particularly from Puntland and Jubaland, while Somaliland continues to assert its autonomy and seek international recognition. In March 2023, Puntland rejected the authority of the federal government over the constitutional reform that would give the President of the federal state more powers. Jubaland contested the feasibility of direct elections due to security concerns and rejected the authority of the federal state. In November 2024, federal and regional courts issued mutual arrest warrants for Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, President of Somalia, and Ahmed Mohamed Islam Madobe, the President of Jubaland state. Tensions, however, reached new heights with direct clashes between federal and Jubaland troops in December 2024.

Decisions about subsidiarity, federalism and elections remain a Somali prerogative that the National Consultative Council (NCC) – a forum established by the president involving federal member states – may help to address. But international partners must avoid deepening divisions by granting economic privileges to competing factions or backing certain regional states in their disputes with Mogadishu. If Somalia’s stability is a priority for its international partners, they should refrain from unilateral actions, which could exacerbate fragmentation. Instead, they should promote the interoperability of security forces, help implement the national security architecture and facilitate political negotiations over contested laws.

This is best achieved through multilateral cooperation, including contributing to AUSSOM and Somalia’s efforts to strengthen its security forces. Any alternative approach risks reigniting widespread conflict, which benefits no one.

Strategic forward

Somalia’s new role as a non-permanent UNSC member offers an opportunity to advocate for AUSSOM funding and better donor coordination. However, in a geopolitical climate marked by competition and contestation, Gulf states, regional neighbours, the EU, and the US should acknowledge that Somalia’s stability remains crucial for maritime trade and counterterrorism.

While bilateralism offers short-term strategic advantages in operating ports, access to resources, and favourable deals, it also risks security fragmentation, and exacerbation of local tensions. In some cases, bilateral arrangements can provide added value by complementing multilateral efforts, as seen in the EU’s support for civilian forces, but they cannot replace the crucial role the AU should play. The AU, Somalia, the UN and the EU have been advocating for enlarging the donor base and ensuring predictable funding for AUSSOM, but other partners should join too. With tensions likely to rise, negotiations may turn into a battle of wills over which donors will shoulder the financial burden.

The EU should remain committed to pursuing multilateral solutions and work to persuade more countries to contribute to AUSSOM’s financing – if not through UN-assessed contributions, then through another financial mechanism such as a trust fund. As Qatar will host a donor conference in April 2025, the EU should support the efforts of the AU and Somalia in engaging Gulf countries and Türkiye in a more multilateral approach. The choice is clear: a fragmented approach risks renewed conflict, while a coordinated strategy offers the best chance to deter it.

Discussion